In January 2021, most of Europe sighed in relief as Joe Biden became U.S. President, bringing an end to the Donald Trump era. Many European leaders struggled to deal with Trump and his way of doing politics, which included pulling out of agreements at the last minute and holding friendly meetings with authoritarian leaders.

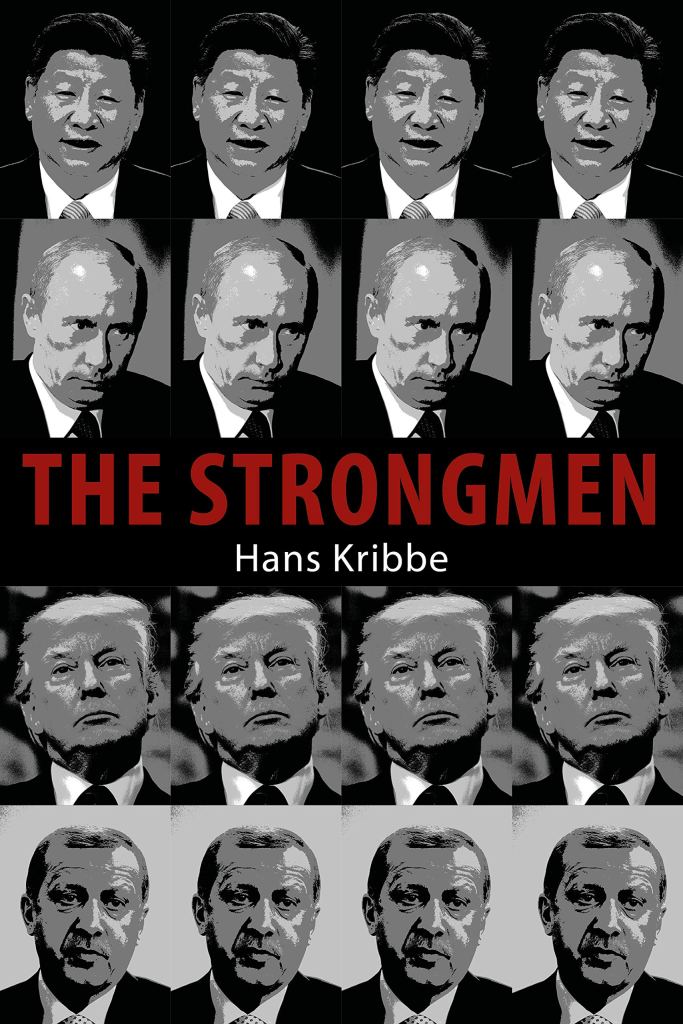

But while Trump is gone from the White House, the type of politics he represents—politics of strength—is here to stay in international relations. And it’s crucial for everyone, especially those who see the world through the prism of rules and values, to understand the leaders who are thinking in terms of power and strength. This is the argument that Hans Kribbe puts forth in his 2020 book The Strongmen: European Encounters with Sovereign Power.

Kribbe rightfully argues that politics of strength are an inevitable part of modern international relations, and that it’s time for the E.U., who is used to talking trade, human rights and values, to understand what the strongman language is all about.

In their recent discourse, officials from both European institutions and member states expressed interest in learning the language of power and developing a more sovereign common foreign policy. In practice, however, it’s obvious that there is a long way to go to these aspirations of becoming a “geopolitical actor.”

High Representative for Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell’s February visit to Moscow, branded a fiasco, is a case in point. Days after thousands of Russians protesting against President Vladimir Putin’s regime were detained, Borrell could not come up with a clear E.U. response, showcasing not only the lack of strategy in European foreign policy, but also the bloc’s inability to speak the language of strongman Putin.

Who is the Strongman?

According to Kribbe, a strongman can appear under several profiles. He could be a lord who bypasses institutions and has an informal social contract with his vassals. If these subjects are disloyal, they can be punished. Think of Xi Jinping’s rivals when he launched a crackdown on corruption in the Communist Party, or Russian businessman Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a Putin critic who was formally imprisoned for tax fraud.

The strongman is also often a performer who uses symbolism and visual elements to demonstrate his popularity, authority and leadership skills, as well the population’s respect towards him. Here, it’s useful to remember Putin’s annual Direct Line television program, where he answers citizens’ questions and solves their problems in a fatherly figure manner.

But as Kribbe points out, none of the key points of the strongman philosophy correspond to the European worldview. During the E.U.’s encounters with strongmen, its identity and usual way of conducting politics were shattered, often preventing it from responding efficiently and having to rely on temporary solutions.

In the 2000s, Brussels realized that its plan for an expanding Union wouldn’t be possible with a neighboring strongman like Putin, who sees the world in terms of spheres of influence. During the 2014 Ukraine crisis, it became clear that making a deal with Putin to end the war was necessary.

In 2015-2016, the E.U. had to ask for help from another strongman, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, on the issue of migration. Up until today, the European strategy is to engage in a dialogue based on human rights and values with Erdogan, while the latter is flexing his muscles both domestically and in the Eastern Mediterranean. The “Sofagate” incident from April’s E.U.-Turkey summit is another illustration of the lack of European unity in response to a strongman like Erdogan.

The E.U. has also had trouble facing Xi Jinping and his plans for China’s renaissance in the form of the “One Belt – One Road” Initiative, which is slowly infiltrating and dividing the bloc. Moreover, for four years Brussels tried to deal with the strongman Trump in all kinds of ways, including education and flattery, only to realize that the projection of a stronger Europe was needed.

Studying Strongmen is Crucial for Europe

Kribbe’s argument should be an eye opener for those who still believe that the world is inevitably moving towards liberal democracy. Around the globe, leaders supporting other models of governance are gaining a level of influence that seems irreversible. Their power depends not on institutions like parliaments and courts, but on their personal skills, informal networks, and deal-making abilities.

As Kribbe points out, in a moment of crisis, when the system is fragile and chaos looms, people often demand a powerful strongman figure in order to keep the order until the necessary institutions—not necessarily those of a liberal democratic model—are ready.

Despite Trump’s departure, strongmen are therefore “expected to be a frequent feature of political order, to appear and again disappear in cyclical patterns,” explains Kribbe. And it’s not possible to deal with them by excluding them, ignoring them, or instructing them about democracy and values.

Something that Kribbe only explores on the surface is how the E.U. can project power in different areas beyond defense and trade. The E.U. could also project its power through its technology and digital policies, its Green Deal and environmental strategy, as well as health policy.

Overall, Kribbe demonstrates that the longer the E.U. continues to ignore the politics of strength and refuses to adopt this language, the more it has to lose in both its credibility and ability to defend its global interests. Failures like the one in Russia show that the bloc still has a lot to learn when it comes to power projection.

Anna Nadibaidze is Editor at Foreign Policy Rising.